Inspired by Te Papa

- Caroline

- Jan 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Te Papa is New Zealand’s National Museum. Somewhat precariously based on the edge of a major fault line in Wellington, its current building opened in 1998. Te Papa is eclectic - it’s not only the National Art Gallery, it’s a natural history museum and a bi-cultural institution showcasing Maori and Pacifica history and art treasures (taonga).

Sadly for me, floor 5, home to the national art collection is closed. It’s been closed for almost nine months due to the discovery of unexpected rust in the sprinkler system. While essential maintenance can’t be helped, I found it frustrating that there is no obvious attempt to relocate the art collection to other floors, or perhaps better still to send it out to regional and local art galleries. Having been to the Sargeant and the Auckland Art Gallery, I noticed a fair few paintings on loan for their exhibitions, but if you compare it to the National Portrait Gallery in London which closed for three years (albeit a planned closure), there’s no active programming to ensure the collection is accessible and on tour.

It is also a little strange that Te Papa is the home of the national art collection. Imagine if the British Museum, the Natural History Museum and the National Gallery combined in London... it's not necessarily a recipe for success! Arguably New Zealand deserves a designated National Art Gallery and its absence has implications and opportunities for the regional art galleries I've ben so impressed by, but that's a debate for another day. There is still plenty to see in Te Papa and it’s given me an opportunity to reflect on what makes Te Papa a world-leading institution and what lessons can be learned for heritage organisations in the UK. .

Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War Review

The star of Te Papa has to be the exhibition Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War. Shamefully I knew very little about the campaign: I thought there was a singular Battle of Gallipoli, not an eight-month siege with 130,842 dead - 86,692 of which were on the Ottomans side. The exhibition is 10 years old now. Originally it was only supposed to be on display for a few years but it's been extended indefinitely.

The exhibition is a masterclass in storytelling. For the vast majority of people, military history is dull. It’s normally map after map, with details on which vantage point, what type of guns were used, different military units and although it’s often gory and harrowing, it’s mostly just very dry. Not so in Te Papa. Having teamed up with the masters of Weta workshop (the creatives behind the weaponry, props and prosthetics of Lord of the Rings), the highlight of the show are the eight massive human figures. At 2.4 times human scale they are huge but with every minute facial and physical detail recorded, they are utterly engrossing and I couldn’t help but expect them to move at any moment. Each sculpture represents a real person, seven men and one woman.

Each sculpture has its own room, complete with atmospheric lighting, sound effects and quotes. We walk in on Lieutenant Spencer Westmacott in mid-shot, wounded and screaming at the enemy. He is the first marker that this exhibition is like no other.

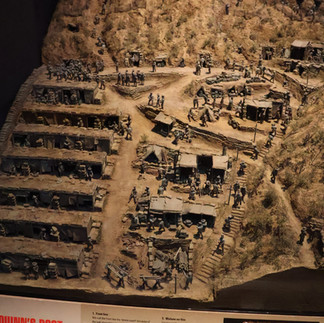

Visitors are guided through the opening days in April of the campaign with a red line of key dates on the floor and a range of stories on the wall panels. There are digital interactive screens to learn more and models of the landscape that light up as a voice narrates the different actions of key dates. There’s an intricate model of Quinn’s Post, a key fortification in the hillside just metres from the Turkish trenches. It adds more colour to the story of Lieutenant Colonel Malone who took charge of reshaping and strengthening the Post so that it could be properly defended and fewer lives were lost. He was a meticulous man and I enjoyed reading diary extracts about how he tidied up his tent site and tried to keep everything clean and orderly. He worked his unit hard and though they resented him in the beginning, his discipline and understanding of military strategy ensured they were much better prepared for the weeks ahead. Tragically, he was killed by a New Zealand artillery fire that exploded prematurely above his trench.

Weapons are displayed in central cabinets, along with a particularly impactful interactive display on how four types of ammunition impacted the body. A digital skeleton is hit by your choice of bullets, shrapnel or a grenade. Another moving part of the exhibition is the alcove dedicated to the May 25th ceasefire to bury the c.3,500 dead men. 3D glasses bring photos of the process to life, as audio testimonies from veterans are played alongside. Subsequent rooms tell the story of poorly designed uniforms, meagre rations, sickness and eventual re-enforcements with the arrival of Maori soldiers.

The exhibition builds to the major August night-time offensive to take Chunuk Bair and break the stalemate. While it’s initially successfully, the Allied’s attempts to hold the high ground are ultimately in vain and many lives were lost. The build up includes walking along a dark, trench-like tunnel, with two video screens on the right cutting to soldiers jumping in to the trench and bayonetting or exploding whoever they encounter. It was less gory than this sounds but I hope you can appreciate the tension and atmosphere as you walk through it, wondering what will be the outcome.

In one very memorable room three Weta figures are firing a machine gun. One is slumped over and the ongoing sounds of gun fire are drowned out by an unseen electrifying Haka (Maori war song).

By November, Kitchener has arrived to Gallipoli and though his purpose is initially a secret, the trip ultimately results in the withdrawal of almost all the forces. 46,000 men are safely evacuated with tricks installed to deflect enemy attention. like guns connected to buckets of water that fill and eventually pull the trigger at random intervals.

Lottie Le Gallais, the only female figure in the show signals a shift in story. As a nurse, she arrived on the Maheno, a medical relief ship that collected soldiers and transported them to Egypt and eventually back to New Zealand. The model replica of the Maheno and the timeline of its various journeys to and from Anzac Bay from Egypt add another dimension to the scale of casualties.

The final figure, Cecil Malthus, closes the exhibition and visitors are invited to write a memory on a paper red poppy and place it on the base of his sculpture. It is a very poignant display and leaves you questioning the purpose of not simply this devastating military campaign but all conflicts.

Nature and Blood Earth Fire

Te Papa has several exhibits dedicated to New Zealand’s Natural History. Nature is an interdisciplinary showcase that takes visitors through marine life, birds, flora & fauna, volcanoes, earthquakes and climate change. Te Papa has a particular focus on storytelling and it’s evident here with interactive displays, colourful exhibits and careful design work.

I particularly enjoyed the Blood Earth Fire exhibit which tells the story of human impact on the land. It starts with the arrival of people from the Pacific before 1300 and follows right through to the modern day. What is undeniable is the increased and overwhelmingly negative impact that European settlers have from the early 19th century. New Zealand’s landscape is dramatically altered with efforts to create more grassland for farming, with vast forests burned and pulled down in the process. The incredible Kouri trees, sacred to Maori, were cut down at an alarming rate as Europeans saw their ‘potential’ for furniture, houses and other items.

But it’s not all bleak. After maps of destruction there are maps of national parks and protected areas. Te Papa points out to its visitors that if we find the loss of wildlife distressing, we can choose to do something about it. Regenerative agriculture offers solutions within the farming industry. I was drawn to a display on Herbert Guthrie-Smith, an English immigrant, farmer and naturalist. His two books proved prophetic with their predictions of environmental devastation but ‘he ended, however, with a positive vision’:

‘The future of man is to make of his life-home an earthly paradise, cleansing its waterways… renewing its forests, watering its deserts, beautifying it with colour and elegance of plant life, reanimating its words with song and movement of birds.’

Having been in New Zealand for over 7 weeks, I have been struck by the continued and determined efforts to fulfil that vision. Zealandia, a huge predator-free 225 ha reserve is a refuge for birds and has ensured that many more species are saved. Walking through the trails there, I was enchanted by the orchestra of bird song and it’s just on the edge of their capital city. We can live alongside our wildlife if we choose to do so. We can enable it to thrive.

What we can learn

This to me is the perfect demonstration of the value of our cultural institutions. Art, history, natural history, science… they do not exist in a vacuum. Museums should not be static; they are sites of inspiration, hope and activity.

What I am learning from the selection I’ve been to is the power of human contact. A tour or just even a conversation is a very powerful thing. In Zealandia, my husband and I showed up with two hours left in the day. Within fifteen minutes of walking through we’d bumped into a guide who took 5 minutes on his way out to cover the history of the predator-free bird reserve, the impact that it has and his personal love for Zealandia. Two days earlier we had been in a tiny Chocolate museum on the east coast. We were about to head in when the lady who had sold us our ticket whipped out a scrapbook and tentatively asked: “Do you know about the cyclone Gabrielle?”

In 2023 the Hawkes Bay area was hit hard by a cyclone/hurricane. Silk Oak Chocolate's cafe, shop and museum were under several square metres of dirty water and mud. The scrapbook detailed their recovery and the colleague showed us photos of the wax figurines in the museum (think Montezuma, Cortes etc) which had been temporarily stored in her house. A waxwork that I would ordinarily have paid little attention to (perhaps even scoffed at if I’m totally honest) was now something to smile at and admire. Our humble entrance fee seemed all the more worthwhile.

Our cultural institutions, no matter what their size, origins or significance, have such power to connect us with each other and with our surroundings. They are markers in itineraries, they tell stories that might otherwise never be told, they teach us about where we came from and inspire us to do better in the future.

Not every museum is going to have Te Papa's budget to put on an exhibition like Gallipoli. I think more should be trying - let's not restrict our ambition - but we can all learn from what makes Gallipoli so impactful:

using personal/individual stories as the base for the main storyline

choosing collection items that link to those personal stories

employing digital and interactive displays that clarify and further understanding, but don't overload with detail

creating games to engage

using sound in addition to lighting to create atmosphere

use scale to convey meaning and magnitude - we cannot appreciate the scale of the Gallipoli conflict but we can get a sense of it by being in awe of a 2.4x human figurine

In the absence of big budgets, more UK museums, galleries and heritage sites should invest in their volunteers and their public-facing staff. We should put on more small-group tours. It was not lost on me that Te Papa had guides in most rooms and they were almost always engaging with people. I think we’d all get more out of many cultural experiences with an expert guide and tours give something to charge a small fee for that supports the longer term economic sustainability of the site. That's not to say we should only have tours, but that we should be bolder in using them. In the end, it will be the person who told us that story that we will remember - not the colour of the walls, the date scone or that huge painting by what's-her-name.

Photos from Te Papa:

Comments